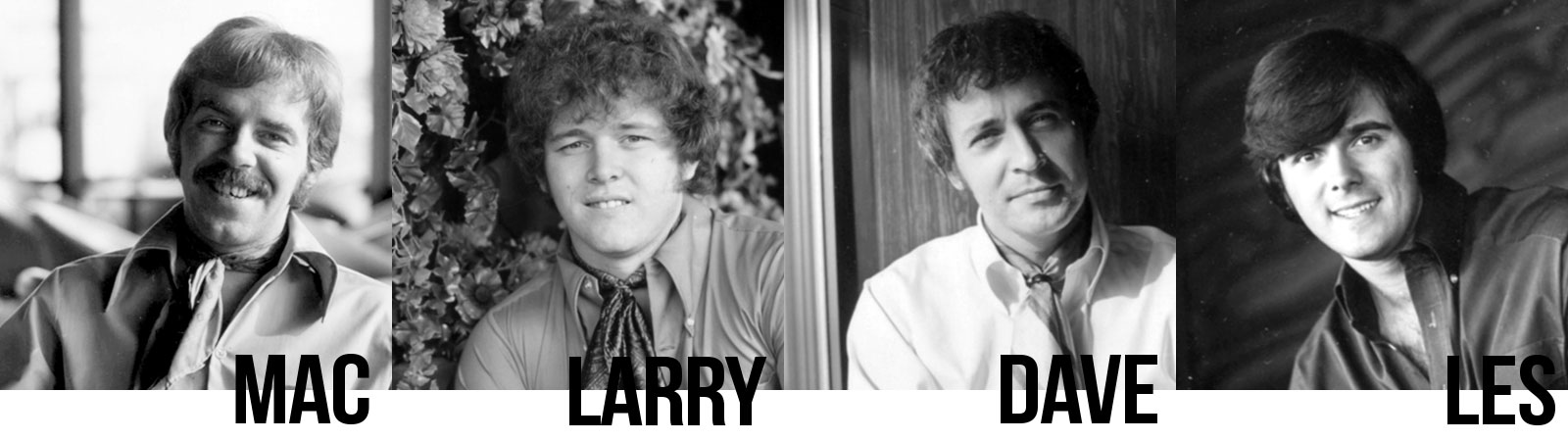

REFLECTIONS: Larry, Dave, Les, & Mac

[This is from a collection of scenes, stories and little chapters that were left on the cutting floor now that Things We Lost In The Night is complete.]

In early 1965, before the guys in my vocal group, the Reflections, left for California in April, we’d tried to develop a little floor show to play in clubs around Indianapolis at Mac’s suggestion. Dave and I had been singing together since high school, but Mac, who had joined us a few months earlier, was already a professional performer. He’d been in the Casinos, a show band from Cincinnati when we met him. They later had a hit with the ballad “Then You Can Tell Me Goodbye.” A few weeks earlier, at our New Year’s Eve party, he told us he was sure we could make some extra money that way. He told us he knew how to perform on stage and could construct little shows for us to do. And though the rest of us shared one single left foot and a clumsy one at that, he swore he could show the rest of us how to do choreography to the songs we already knew. I had serious reservations about that. We’d rarely performed publicly, we didn’t play instruments, and my wife, Pat wasn’t thrilled about the idea… and I tended to freeze up in front of audiences. But for many of the guys, it made sense, especially when Mac called the agent for his ex-band, the Casinos, who later had a big hit with “Then You Can Tell Me Goodbye,” told him she could book the band if we would do a few out-of-town gigs to tighten up the band.

Les, who’d expected to be our guitar player, became our last-minute replacement bass singer a couple of weeks before our first booking in Birmingham, Alabama at some place called the Boom Boom Room. Since Les was going to sing with us and not play guitar, we needed musicians to back us up. Les found a little outfit called the Zeb Miley Trio playing in a downtown Indianapolis bar called Susie’s Twist Club. They agreed to go on the road with us for a few weeks to tighten up our show. We renamed the combined band and singers, the Checkmates, and ill-fated choice as it turned out, but that is a different story.

At some point I’ll post something about our adventures at the Boom Boom Room right in the middle of the civil rights marches going on at the time, about how dangerous it had been including threats from the audience for not playing the right music and accusing one or another of us of sleeping with somebody we shouldn’t have, and a bomb threat — but I thought I’d like to post this little bit from the Can Can Room, the next club we played in St. Louis, Missouri, first.

The Checkmates – The Can Can Room

Monday, March 1, 1965, St. Louis, Missouri

We walked out into the cold Missouri night to find Zeb Miley and Johnnie Lamb in a heated discussion with a portly older man in a navy blue suit with an open-collared white dress shirt. The heavyset man was poking Zeb in the chest while Johnnie was walking around in little circles looking at the ground. When I walked up the man was saying in a cloud of frosty breath, “. . . what were you thinking, that you could walk into this club on Union paper with non-union musicians in your band? What kind of idiot are you?”

“What’s happening?” I asked.

“Musician’s Union bullshit,” Zeb said. “The usual union crap. As usual, they do more to stop you and then help you get work.”

“You know,” the man said to Zeb, “you should be thanking me. I could yank all of you off the stand right now. Yes I could. Club operator would never have another union band in this joint if they didn’t comply.

“Half your band,” he went on, waving his hand around, “is behind in their dues and the other half,” waving his other hand, “don’t have any union cards at all.”

Zeb turned to me, frowning and said, “He’s the local union rep and he’s saying you guys ain’t union so you can’t go back on stage.”

“You,” the man said, turning to make me his center of attention. “Whatinhell do you think you are doing up there without a union card?” While belligerent, he also seemed a little perplexed.

“Why would I need a union card,” I said, even more perplexed. “Why would singers need to belong to a musician’s union? We don’t play instruments.” I looked at Zeb trying to comprehend what was going on.

“If you sonsabitches are on that stage, you gotta have a card, period.” Mr. blue suit insisted.

“We just played in Birmingham, Alabama last week, before we came here. No one said anything about union cards to us.”

“Do you know where you are, sonny? Do you now?”

“Yes sir. This is St. Louis, Missouri. And it’s a beautiful city,” I added.

“And, does that mean anything to you, music-wise? Ring any bells?” he continued smugly.

I looked around for a lifeline but no one else seemed to have a clue, either. “Nosir I don’t.

“Well, you ignorant SOB, this is Local #2 of the Musician’s Union of America. Now I suppose you’ll have to tell me that you don’t know what that signifies, won’t you?”

I shook my head no. I had failed so many classes in school and now here I was again, failing Musician’s Union 101 this time, dammit.

“No?” he said, continuing to rub it in. “No, you still don’t know? Well, I’ll tell you. We were the second local union formed, right after New York City. This is probably the strongest local in the United States. You do not fuck with St. Louis Union Local #2. Do you understand that?”

“Yes, but I don’t see …”

“No pissant city like Birmy-fucking-ham, Aly-fucking-bama decides whether you need a union card in St.-fucking-Louis. Is that clear?”

“Okay. Okay,” Mac said, “We get it.” By this time, Dave had joined us on the street. Drivers and passengers in the cars passing us by were looking at us. It was freezing out here. “But,” Mac continued, “We don’t play instruments. I don’t get how we have to belong to a union?”

“So you don’t play an instrument, you say, even though I say, if you step on the goddamn stage in there you got to be union. Well, let me ask you something sonny boy. What was that funny metal thing you was tootling around on while ago marching around that club like a loon? What was that anyway? Looked suspiciously like a saxophone, of course, I could be mistaken. Maybe you was playing the radio,” the Union rep grinned.

“Aw that was nothin’. I don’t really play sax. I just tote that thing around when we’re doing this dancin’ thing. Can’t play but two notes. You can’t count that,” Mac protested.

“And where’s that tall boy,” the rep continued. “Oh, here he is right here. I don’t suppose you play that trombone though you was pushing that slide back and forth like you knew what you was doing. You just another mummer, too?”

“Hell, I just got here,” Dave said, “I got no clue what’s going on. I play a little trombone. I’ll tell you how much though, damn little.”

“Damn little is plenty enough,” said the man as he turned to me. “And then there is you. Yes, you were banging two pieces of wood together so I expect you’re going to tell me you weren’t playing an instrument either. That so?”

“Yeah, I mean no, I don’t think so …” I said, wondering a bit.

“Claves,” he said. “those pieces of wood are called claves, they’re South American musical instruments my fine young friend so you and all the other guys without union cards, including the last guy who had a guitar strap on last time I saw him are not in compliance with union rules and regs. I can fine your asses up to $500 apiece.”

I went white. “Why that would end it for us. We’re just trying to get started. This is only our second job. That’s not fair. That can’t be what the union is for,”

“Fair, did you say. Well, fair is as fair does, and Zeb Miley here, well he’s the leader of this group. He knows the rules and he’s the one that broke ‘em. I’ll likely be pulling his card tonight and he’ll have to attend a hearing in a couple of weeks to find out how much it will cost to get it back. If he can get it back,” the rep said with finality.

We were all well and truly cowed and intimidated. “Is there some way we can make this right?” I asked. Zeb threw his hands down in disgust and turned away. “We weren’t trying to avoid anything. Really, we just didn’t know.”

“I dunno,” he said, looking around at us. “Some of you don’t seem so willing to see the error of your ways.”

“C’mon guys,” I said to everyone on the street. Scott and Les were still inside somewhere. “Please, Mr ….” I started. I didn’t even know his name.

“I am Jonas Lawndale,” he said, “and here is my card. ‘Bout time somebody asked if I was legit.”

“Mr. Lawndale, we are a young band, just trying to get a foothold. If you could see your way to give us some leniency and help us find a way through the mess we’ve made here, we’d appreciate it.” I said.

“Well sir, Mr. Miley,” Mr. Lawndale gestured in Zeb’s direction. “Does this fellow here have the right of it or do you continue to take exception to my pointing out your failings here? You are the rightful leader, signed onto this contract, and it is in your hands.” He stuck his chin out toward Zeb.

Our looks at Zeb must have conveyed enough fervor for him to get the message.

“Yeah, yeah, I know we’re in the wrong,” said Zeb with difficulty. He thought about it a bit and then said, “I didn’t rightly think these singer guys would have to be in the union especially as they don’t sing but 10 songs a night. But it’s so that a couple of us are late on our dues, so yeah, we need your help if you’d be offering.”

“Hmmm,” hummed Mr. Lawndale, seeming to figure what he would say to us. “First off those ‘singer guys’ as you call them, they ain’t going back on that stage tonight and not again ‘til they got union cards.

We didn’t say anything. Thank God, we’d finished our second show. There was one more set to go but we were finished for the night.

“Now I’m willing to forget about the fines for ya’ll since you’ve explained so nicely about where your confusions was, and I’ll forget about them late fees as well, but all you union guys got to have your cards up to date starting tomorrow night. And I am firm about that.

“By the way, it does seem that one Mr. Lamb does seem to be up to date so he can play it seems.”

“Mr. Lawndale,” I asked as gently as possible, “What does it cost to join Local #2 of the Musician’s Union of America?”

“Well son, I believe we can make you a member for $150 tomorrow down at the union house.” Jonas Lawndale beamed.

“Wow!” I said, stunned. “Wow!” I repeated since I couldn’t think of anything else to say.

“We belong to a different Local, Mr. Rep,” Zeb said, a bit sourly, so do we have to pay our fees on Local #2’s schedule?” I think Zeb had already forgotten the union rep’s name.

“Well, Mr. Zeb Miley, we at Local #2 have a great fondness for our brothers across this great land and so, in token of that respect, we honor paying fees that we forward to those locals. So, in short, you must pay, down at the union house, the fees appropriate to your schedule at your home local.” Mr Lawndale added, “If you decided that you wanted to change your affiliation to the best and strongest union in this United States, while I’m sure we could get you a significant discount, however.”

“Well, then, Mr. Rep, we will get us into compliance first thing tomorrow. But I also reckon we better get ourselves into that club and finish our last set or we won’t have no job to save.” Seeing Mr. Lawndale’s look he added, “And that means without them singers. I know.”

“You will be seeing me tomorrow night, Mr. Miley. I give you fair warning, though, should you fail in any respect to meet the stipulations I have given you, I will not be so easily swayed as I have been tonight.” Mr. Lawndale turned without another word and walked into the night.

“Damn, where are we going to get $150 each?” I said to Dave and Mac despondently?

Before Zeb headed into the door, he said, “That’s not the hard part. You guys can run back to Indy tonight and get union cards for $35 in the morning and be back in time for your first show. The big problem is your guitar player. Boy is underage and I don’t know if he can figure a way to get hisself a union card. You better check with him about that.”